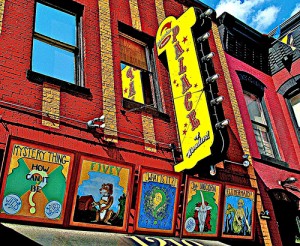

Flickr: Elvert Barnes

From the DC Emancipation Day Voting Rights March 2007

Tomorrow is Emancipation Day in the District; for most, that means an extra weekend for tax preparation, but it’s worth considering why tax day was delayed this year (and every year when the holiday falls on a Saturday). On April 16th, 1862, slavery ended in the District nine months before President Lincoln would go on to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

The District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act freed almost 3,000 enslaved people while compensating their former masters for the loss of their human property– the only example of compensation by our federal government to former slave-owners.

From the National Archives:

The act brought to a conclusion decades of agitation aimed at ending what antislavery advocates called “the national shame” of slavery in the nation’s capital. It provided for immediate emancipation, compensation to former owners who were loyal to the Union of up to $300 for each freed slave, voluntary colonization of former slaves to locations outside the United States, and payments of up to $100 for each person choosing emigration. Over the next 9 months, the Board of Commissioners appointed to administer the act approved 930 petitions, completely or in part, from former owners for the freedom of 2,989 former slaves.

The act fundamentally altered D.C., where previously, all free and enslaved black residents had to adhere to a strict 10pm curfew or face arrest and torture.

No longer downtrodden, the first freed slaves in the country created the city we know today:

Escaped slaves from Maryland, Virginia, and beyond—as many as 40,000—poured in, colonizing the neighborhoods and building the institutions that would form the foundations of today’s black community.

Less than a decade after the Civil War, an African-American newspaper—hailing the participation of blacks in local government, the passage of civil-rights laws, the founding of Howard University, and the establishment of thriving (though segregated) public schools—would declare: “Probably to a greater extent than elsewhere in the country is the equality of citizens in the matter of public rights accorded in the District of Columbia.” The sounds of the curfew bell and the slave auctioneer’s hammer were fading memories.

Continue reading →