October 14, 2011 | 8:00 AM | By Elahe Izadi

A Look Back: Lincoln Theatre and Black Broadway

FILED UNDER: History, Black Broadway, Lincoln Theatre, U Street

The Lincoln Theatre is approaching its 90th anniversary as a cultural beacon of the U Street district. But impending closure threatens to break an important chain in D.C. history.

The theater opened in 1922 at 12th and U Streets, at the height of the racial ghettoization of D.C. Although the District outlawed Jim Crow laws in 1917, segregation became a reality in D.C. Racially restrictive housing covenants and Depression-era laws ended up restricting housing and services to non-whites in certain neighborhoods.

In the face of this, U Street evolved into Black Broadway, an inimitable nexus of businesses, civil institutions, entertainment venues and homes. The area first experienced a boom after the Civil War, as thousands of new residents moved from the south. Between 1900 and 1948, U Street proved a vital epicenter for those suffering under the legacy of slavery.

The Lincoln Theatre was a luminous cornerstone in the grim shadow of segregation, a place where those ostracized by much of the country had a bright future. Tennis star Arthur Ashe recalled the 1940s on U Street: “The cream of black society and everybody else passed through there… You always had the sense that something big was about to happen.” As Teresa Wiltz put it in her evocative 2006 Washington Post article, “With U Street, black D.C. could lay claim to a world that was, to borrow a phrase of the hip-hop generation, ‘for us, by us.’”

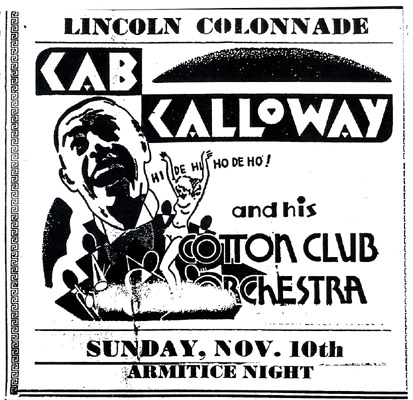

The theater was one of a number of such venues built in D.C. by two ill-fated white entrepreneurs. The Lincoln thrived when it opened, first as a first-run silent film and vaudeville house, then in 1927, when it became a luxurious cinema venue with a ballroom downstairs. Proprietor Abe Lichtman brought huge names to the theater including Count Basie, Eleanor Roosevelt and Bess Truman, which eventually paved the way for the likes of Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughn.

For forty years the Lincoln reigned as an institution of U Street nightlife. That changed on April 4, 1968, the day of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. As the devastating news spread, crowds formed on the streets of downtown D.C., with outrage and sadness gradually twisting into violence and rioting. D.C.’s landscape would be radically altered for the next 30 years a result of the damage from the riots. U Street businesses were hit hard and wealthy and middle class people fled to the suburbs. Likewise, the Lincoln fell into disrepair and disuse, finally shutting its doors in 1981.

Then in 1989, the theater received $4 million in federal money toward its $9 million restoration. The Lincoln reopened in 1994, marking a turning point for the Columbia Heights, Shaw and U Street districts, which have undergone revitalization in recent years. These areas were back in business, with the Lincoln once again at the forefront.

But the Lincoln has been plagued by financial woes in recent years. It almost closed due to low funds in 2007, the year it became a historic landmark and property of the city. The city gave it $1.5 million for capital improvements to fix the roof and plumbing. But it once again faces closure. Without at a boost of at least $500,000, the theater will close by the end of the year.

Mary-Alice Farina is a writer for 365DC. Read her in-depth Lincoln Theatre history here and follow her on twitter at @mafalicious.

MORE POSTS ABOUT

- History

- Lincoln Theatre

- U Street

-

DCentric Picks: Emancipation Day Great Debate

What: D.C. Emancipation Day Great Debate When: 6 p.m., Saturday Where: The Lincoln Theatre, 1215 U St. NW Cost: Free, but you should register here. Why you should go: The debate is just one of a number of D.C. Emancipation Day activities taking … Read More

- Anniversary of MLK Assassination And The Riots That Changed D.C.

- Do We Still Need Black History Month? (Poll)

-

DCentric Picks: Emancipation Day Great Debate

What: D.C. Emancipation Day Great Debate When: 6 p.m., Saturday Where: The Lincoln Theatre, 1215 U St. NW Cost: Free, but you should register here. Why you should go: The debate is just one of a number of D.C. Emancipation Day activities taking … Read More

- Lincoln Theatre, Fixture of Black Broadway, To Close

-

When Early Gentrifiers Can't Afford to Stay

Businesses move to transitional neighborhoods because space is cheap and there’s potential for future growth. But sometimes the economic success of these neighborhoods leads to the demise of the early gentrifiers. Love Cafe opened at 15th and U Street, NW … Read More

- D.C. May Lose One of the Last Remnants of Black Broadway

- Lincoln Theatre, Fixture of Black Broadway, To Close